Can You Take Me Higher? What You Need to Know about the U.S. Debt Ceiling

Filed in: Finance Industry, Industry News

If the current debt ceiling debate were a song, the chorus from this 1999 Creed tune, “Higher,” could be its theme.

“Can you take me higher?

To a place where blind men see

Can you take me higher?

To a place with golden streets.”

The debt ceiling is the maximum amount the U.S. government can borrow by issuing debt securities, including U.S. Treasury Bonds. The ceiling imposes a statutory borrowing limit on Congress, to make sure our borrowing does not exceed our ability to pay the debt back.

We recently reached our debt limit, which stands at $31.4 trillion. The natural question is, what happens next?

The economic ramifications of decisions resulting from the current debate about whether or not to raise the debt ceiling will impact inflation, jobs, production, and spending. Let’s dive into the history of our debt ceiling and what’s next.

When Was the Debt Ceiling Created?

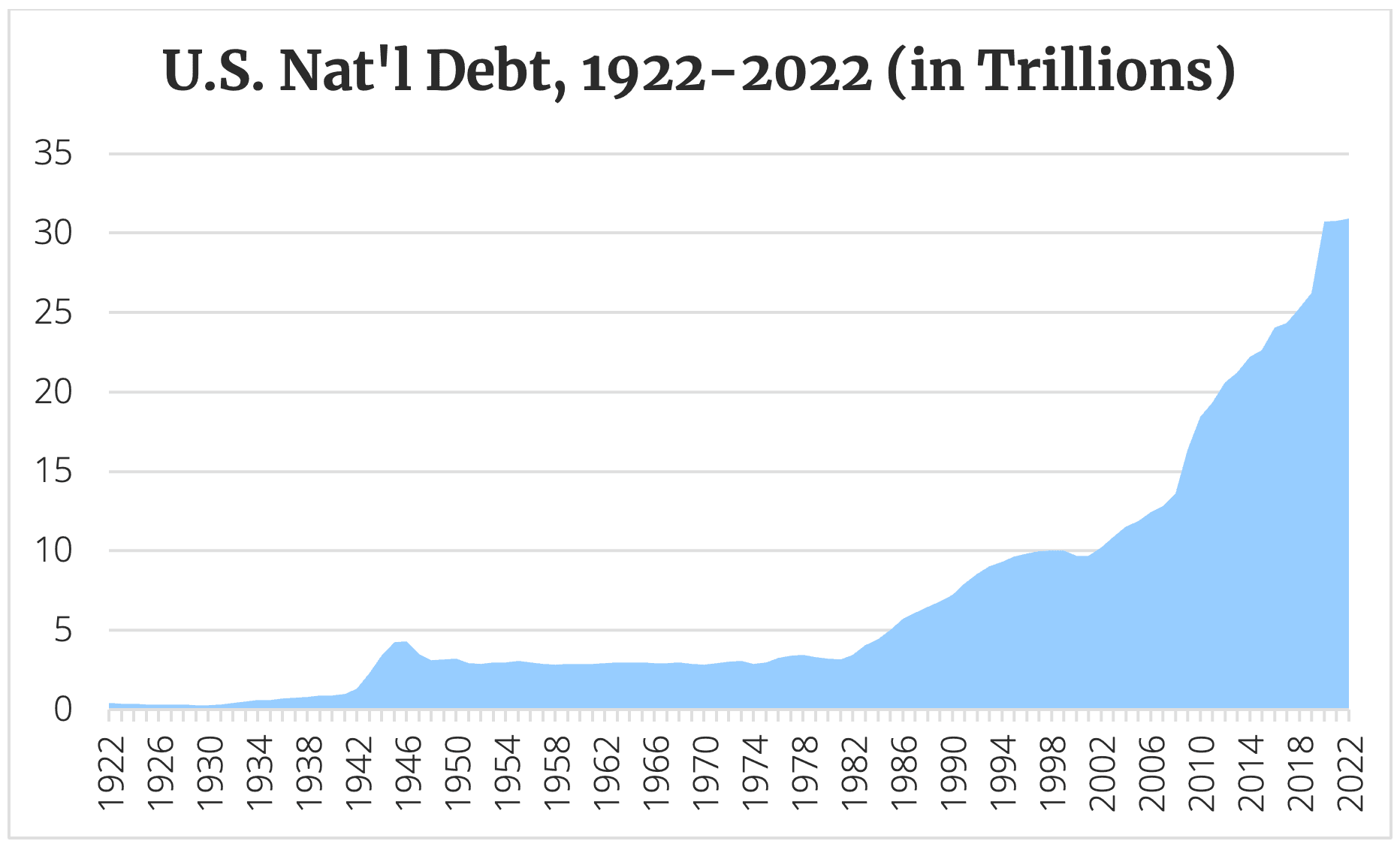

The U.S. debt ceiling was created more than a century ago by the Second Liberty Loan Act of 1917 to raise $3 billion to support our European allies in World War I. Those bonds matured 25 years later with a 4% annual coupon or nominal yield. How has our debt grown since that time? It skyrocketed during periods of economic difficulty, war, and the global pandemic.

- The U.S. National Debt, representing total U.S. debt obligations to Treasury debtholders, reached $1.32 trillion in 1942, during World War II.

- The debt ceiling reached $4.28 trillion in 1946 and stayed relatively low for the next 36 years, until 1982.

- The debt ceiling has always increased; never decreased. Recently, those increases have been dramatic, leading to temporary suspension and cap at $22 trillion in 2019, the onset of the global pandemic.

- Borrowing rose 662% for the 40 years between 1983—2022, recently reaching the debt ceiling of $31.4 trillion.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

How Credit Card Debt Illustrates the Debt Ceiling

Imagine negotiating a higher spending limit on a personal credit card. This extra spending power in the monthly budget may be nice, but increasing that limit comes at a cost. Carrying that larger card balance will increase your monthly interest expense, which reduces income for other needs. Increasing your spending will result in you reaching a new credit limit. That means that if you keep up that expanded lifestyle, you will need to negotiate an even higher credit limit.

Any possibility of reducing the card balance becomes a long-term endeavor. In the short term, it is only realistic to pay interest on the outstanding balance. The household has the complex conversation of finding additional income, making spending cuts, or both. Each member has different priorities. Since reaching a consensus on where to cut back is difficult, the conversation may stall.

Meanwhile, recurring household expenses must be funded. Since spending still exceeds income, periodic credit limit increases will be the new normal. This cycle ends in one of two ways: reducing your spending or defaulting.

Why the Debt Ceiling Keeps Getting Higher

The credit card analogy illustrates the cycle of federal borrowing and spending in recent years. Periodically, our federal government must raise its debt ceiling to continue funding its obligations—such as social programs and interest on our debt, defense. That’s because the U.S. government operates through deficit spending. The government spends more than it receives in revenue and funds the difference through borrowing.

Each time we reach our debt ceiling, debate ensues among our national leaders about whether to increase taxes or cut spending, until consensus is reached, allowing the vote to raise our limit. Each time, consensus seems more difficult to achieve, fanning uncertainty and fear in U.S. and global financial markets.

What Would Raising the Debt Limit Mean?

Increasing the debt limit means increasing debt per capita for every American (and future Americans), in effect, “kicking the can down the road.” Raising the limit would allow the country to maintain federal operations and our national lifestyle. It would provide a stop-gap solution but not a long-term solution to the country’s spending, tax policy, and economic priorities.

Not raising the debt limit and defaulting would have negative economic effects. The result of such an unprecedented event would certainly be negative. Borrowing rates for our country and every citizen would skyrocket. Seniors’ and veterans’ income and medical care would be interrupted. We could plunge into a deep recession. Financial markets would experience upheaval.

The debate over our national debt ceiling is not a distant, academic exercise. The ramifications of the decision over whether to raise the debt ceiling will impact inflation, jobs, production, and spending. It is a crucial exchange with a far-reaching impact on all Americans.

Written by Cass Garner

Cass Garner is a member of the Knopman Marks faculty. He brings a wealth of experience to the role, including work at FINRA performing compliance examinations, teaching at Kaplan, and working at National Regulatory Services (NRS). He has passed licensing exams, including the CPA exam, license exams for insurance and real estate, and many FINRA exams. Helping students develop their potential is what drives Garner. He lives for those ‘aha’ moments when he can guide a student so that things click, and they understand a concept.

Related posts

- Read more

The SIE Advantage: How College Students Can Get a Head Start in Finance

As a rising senior at Fordham University, Harmonie Chang’s decision to tackle the Securities Indu

- Read more

SEC Shortens Settlement Cycle for Most Securities to T+1: Updates for Exams Going Forward

The SEC has officially updated the rules to shorten the standard settlement cycle for most securi

- Read more

2024 FINRA Annual Conference Recap

Our team traveled to the FINRA Annual Conference in Washington, DC last week and wanted to share